For decades, the topic of bioplastics based on renewable raw materials has been a story of unfulfilled hopes for the packaging sector. The new PPWR could now get things moving. It does so through the back door, so to speak, and in the (foreseeable) event that the recyclate utilisation quotas stipulated in the PPWR cannot be achieved. The regulators have therefore already turned their attention to bioplastics from renewable sources. They are to serve as a stopgap to achieve the sustainability targets. But is this realistic? Do these plastics even have the potential to fill the quota? And if so, which ones – and by when?

The PPWR as a driver?

Article 7 of the new Packaging and Packaging Waste Regulation (PPWR) deals with the topic of the minimum recycled content in plastic packaging. Even if it may not be obvious at first glance, this is a potential driver for the market and the use of bio-based polymers. This is because the introduction and, above all, the fulfilment of prescribed quotas for the use of recyclates in food applications is closely linked to the issue of chemical recycling.

Specifically, paragraphs 1 and 2 of Article 7 define minimum percentages of recycled materials obtained from consumer plastic waste for the target years 2030 and 2040.

The crux of chemical recycling

However, the question arises as to whether the required quantities of recyclate can be made available at all. Much depends on whether and which forms of chemical recycling are authorised for the production of recyclate.

- The EU Commission is to present a legislative proposal by 2028 (or 3 years after the PPWR comes into force).

- Should no suitable recycling technologies for food contact packaging be available by then, which meet the requirements of Regulation (EU) 2022/1616 and ensure the necessary quantities of recyclate, the only way out would be to cover the sustainability requirements using bio-based raw materials instead of recycled content from consumer plastic waste (Article 7a).

In concrete terms:

- By 2028 [3 years after the entry into force of this Regulation], the Commission shall review the state of technological development and the environmental performance of bio-based plastic packaging, taking into account the sustainability criteria set out in Article 29 of Directive (EU) 2018/2001 (bioenergy).

- Where appropriate, the Commission shall, on the basis of this review, submit a legislative proposal to:

- establish sustainability requirements for bio-based raw materials in plastic packaging;

- set targets for the increased use of bio-based raw materials in plastic packaging;

- introduce the possibility of achieving the targets set out in Article 7(1) and (2) of this Regulation by using bio-based plastic raw materials instead of recycled content from post-consumer plastic waste in the absence of appropriate recycling technologies for food contact packaging that fulfil the requirements of Regulation (EU) 2022/1616;

- amend the definition of bio-based plastic in Article 3(41b) if necessary.

A way out for “linear” quota fulfilment?

Even if this “way out” would certainly not be circular in the sense of the circular economy, it would at least (somewhat suddenly and unexpectedly) offer a way out to fulfil quotas, which would at least force the desired further reduction in the use of fossil raw materials. But what exactly is the situation with recyclates and bioplastics?

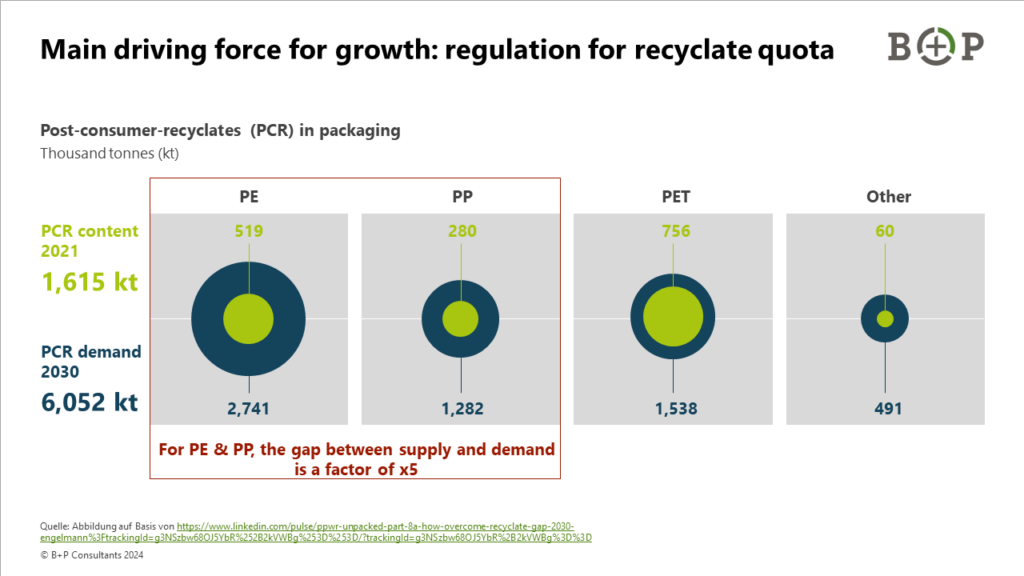

Recyclate: quantity and availability

It was not least the plastics industry that continuously pointed out at an early stage that in order to fulfil the quotas in the area of food contact applications, a fivefold increase in the currently available PCR quantities would be required by 2030, especially for the mass plastics PE and PP. In addition to quantity, there is also the question of availability for the packaging industry.

- The question of the quantities of PCR that will be available from chemical or “advanced” recycling in 2030 can hardly be answered with any certainty today. Much depends on which processes are approved for the production of recognised recyclate or will be approved by then.

- There is also the question of whether the corresponding PCR material is even available and affordable for packaging in competition with other industries such as household appliances or consumer electronics.

Does bioplastic have the potential to become a quota filler?

So bioplastics? The question is whether development here is already far enough advanced to serve as a quota filler.

- Bioplastics are currently being used for an increasing number of different applications. These range from packaging and consumer goods to electronics, automotive and textiles.

- However, according to the nova Institute, packaging will remain the largest segment for bioplastics in 2023 with a market share of 43%.

- 5 Bioplastic polymers cover more than 90% of the total global production capacity for packaging applications:

- PLA,

- PE,

- SCPC,

- PBAT (renewable or fossil-based) and

- PHA

- If we look at mass plastics that could be used directly as “identical” drop-in materials, the relevant availability is currently limited to bio-PE.

PE: Example Tetra Pak and Braskem

In 2014, Tetra Pak launched the first “Tetra Rex” on the market. The beverage carton is advertised as the world’s first and only beverage carton packaging made exclusively from renewable raw materials. Bio-based PE is used as the closure material.

- By 2022, Tetra Pak has delivered more than half a billion packages of Tetra Rex® Plant-based, the world’s first beverage carton made entirely from renewable materials.

- Since 2019, Tetra Pak, together with its supplier Braskem, has been the first company to use responsibly sourced plant-based polymers based on the Bonsucro standard for sustainable sugar cane.

- Braskem has been driving development as a global market leader since 2010 and also supplies the European market with its sugar cane-based bio-PE.

- The company recently announced further investments for its bio-PE as part of a joint venture with SCG Chemicals. The partners plan to produce 200,000 tonnes of bio-based polyethylene annually in Thailand under the I’m greenTM

- Braskem is currently evaluating the options for bio-based polypropylene. However, this also means that no bio-based solution for the mass plastic PP is to be expected in the short term.

PEF as a beacon of hope?

The question of whether PEF (polyethylene furanoate) is not the better PET has been discussed for some time. In fact, PEF could have enormous potential in the packaging, textiles and films sectors. These are growth markets with a value of over 200 billion dollars.

- The main building block of the bio-based polymer is FDCA (2,5-furandicarboxylic acid) and is obtained from sugars from wheat, maize or sugar beet.

- When the technology is fully developed, PEF will also be produced from cellulose and thus from agricultural and forestry waste streams.

- PEF is the main product of the Amsterdam-based company Avantium, which sees itself as a pioneer in the emerging sector of renewable and sustainable chemistry.

- PEF is marketed as a novel, plant-based and recyclable plastic with a powerful combination of environmental and performance characteristics. According to the nova-Institut, PEF has improved barrier properties compared to PET, is mechanically and chemically recyclable and can also be recycled as part of the established PET recycling process.

- The substitution of PET in bottle production is seen as a “killer application”. In addition, paper-based bottles are also to be coated with barrier PEF.

- The world’s first commercial FDCA plant is due to go into operation this year.

The situation with compostable plastics

A regulatory boost for biodegradable or compostable plastics is not expected in Europe. However, PLA, starch-based polymers and PBAT have shown a clearly positive development in this segment.

However, their significance in a circular economy also depends on their recyclability and the sorting and recycling solutions required for recycling. These are not yet in sight.

Conclusion

- For decades, the topic of bioplastics based on renewable raw materials was a story of unfulfilled hopes for the packaging sector. Unlike in the automotive industry (bioethanol), for example, there has never been a growth driver in the form of regulatory support.

- The recognition of bioplastics based on renewable raw materials as “quota fillers” expressed in the PPWR could be a game changer – even if only for drop-in materials.

- It is also to be expected that no further capacity expansions will be initiated by the industry until the EU’s decision in 2028, apart from those already announced.